What You Need to Know

- A deal could lead to large sales of Treasury bills, hurt bank liquidity, push short-term rates higher and tighten the screws on a weak economy.

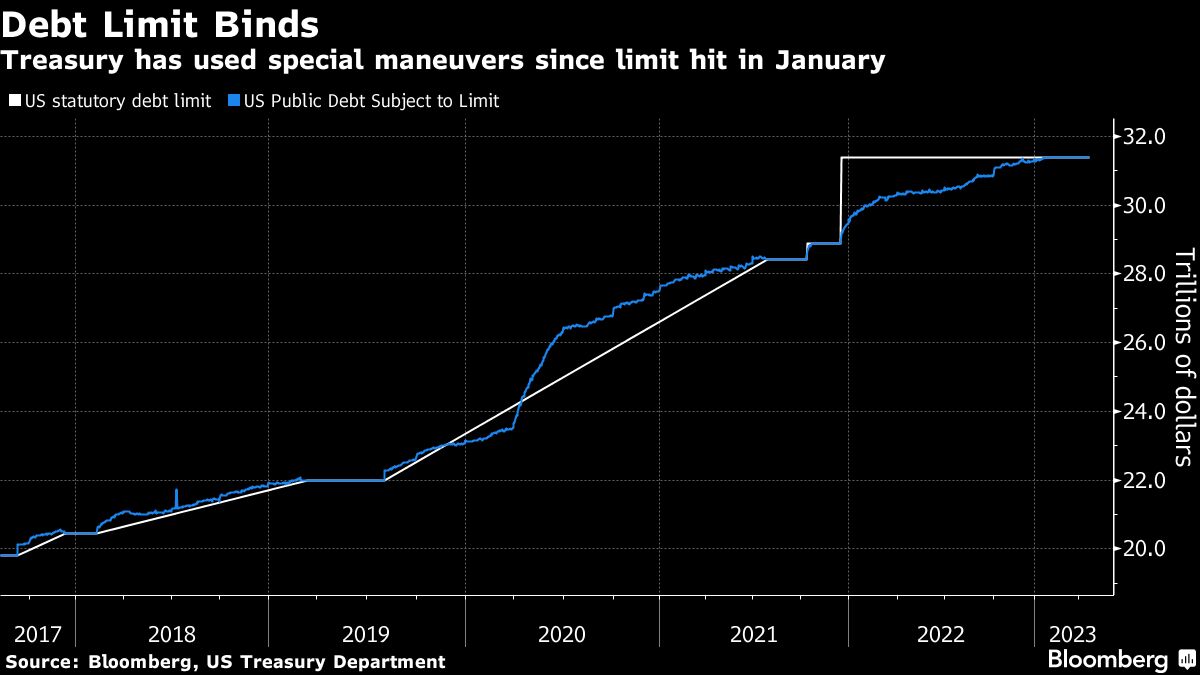

Looming behind market fears over the prospect of a historic U.S. default is the less-discussed risk of what would follow a deal to resolve the debt-ceiling impasse.

Many on Wall Street predict lawmakers will ultimately reach an agreement, likely averting a devastating debt default, even if it goes down to the wire.

But that doesn’t mean the economy will escape unscathed, not just from the bruising standoff but also as a result of the Treasury’s efforts to return to business as usual once it can ramp up borrowing.

Ari Bergmann, whose firm specializes in risks that are hard to manage, says investors should hedge for the aftermath of a Washington resolution.

What the market veteran is getting at is that Treasury will need to scramble to replenish its dwindling cash buffer to maintain its ability to pay its obligations, through a deluge of Treasury-bill sales.

Estimated at well over $1 trillion by the end of the third quarter, the supply burst would quickly drain liquidity from the banking sector, raise short-term funding rates and tighten the screws on the U.S. economy just as it’s on the cusp of recession.

By Bank of America Corp.’s estimate it would have the same economic impact as a quarter-point interest-rate hike.

Higher borrowing costs in the wake of the Federal Reserve’s most aggressive tightening cycle in decades have already taken a toll on some firms and are slowly crimping economic growth.

Against this backdrop, Bergmann is especially wary of an eventual move by Treasury to rebuild cash, seeing potential for a massive reduction in bank reserves.

“My bigger concern is that when the debt-limit gets resolved — and I think it will — you are going to have a very, very deep and sudden drain of liquidity,” said Bergmann, founder of New York-based Penso Advisors. “This is not something that’s very obvious, but it’s something that’s very real. And we’ve seen before that such a drop in liquidity really does negatively affect risk markets, such as equities and credit.”

The upshot is that even after Washington gets past the latest standoff, the dynamics of the Treasury’s cash balance, the Fed’s portfolio-runoff program known as quantitative tightening and the pain of higher policy rates all stand to weigh on risk assets as well as the economy. And a deal is looking more likely.

The upshot is that even after Washington gets past the latest standoff, the dynamics of the Treasury’s cash balance, the Fed’s portfolio-runoff program known as quantitative tightening and the pain of higher policy rates all stand to weigh on risk assets as well as the economy. And a deal is looking more likely.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said Thursday that negotiators on the federal debt limit may reach an agreement in principle as soon as this weekend and that he expects his chamber to consider a deal by next week.

After a debt-cap resolution, the U.S. cash stockpile — the Treasury General Account — should soar to $550 billion as of the end of June from the current level of about $95 billion — and hit $600 billion three months later, according to the department’s most recent estimates.

A rebound will affect liquidity across the financial system because the cash pile operates like the government’s checking account at the Fed, sitting on the liability side of the central bank’s balance sheet.

When the Treasury issues more bills than it technically needs during a certain period, its account swells — pulling cash out of the private sector and storing it in the department’s account at the Fed.

Another important piece of the puzzle is the Fed’s reverse repurchase agreement facility — dubbed the RRP — which is where money-market funds park cash with the central bank overnight at a rate of just over 5%.

May 18, 2023 at 02:45 PM

May 18, 2023 at 02:45 PM

“The Treasury has to rebuild their slush fund,” which “removes liquidity from the system,” Jerome Schneider, head of short-term portfolio management and funding at Pacific Investment Management Co., said on Bloomberg Television.

“The Treasury has to rebuild their slush fund,” which “removes liquidity from the system,” Jerome Schneider, head of short-term portfolio management and funding at Pacific Investment Management Co., said on Bloomberg Television. Copyright © 2024 ALM Global, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2024 ALM Global, LLC. All Rights Reserved.